DETERMINING WHETHER PROBLEMS EXIST

GRIES ASSESSMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL PERMANENCE (GAPP)

In my December 12th blog, I introduced the construct, Psychological Permanence, to help us understand the underpinnings of emotional health in the developing child. A broadened definition of Psychological Permanence includes the following elements:

· Psychological Permanence reflects the inner, subjective state of a child, who feels s/he belongs and is at peace with his/her place in one or more families with which s/he identifies.

· Psychological Permanence is a state of emotional balance or homeostasis, which is durable over time and across events; it may be subject to periodic relapse or destabilization due to developmental factors and/or significant new traumatizing events, but recovery is swift and full.

· Psychological Permanence reflects resolution of inner conflict concerning separation from one or both birth parents, and about attachment to custodial as well as non-custodial caregivers.

Psychological Permanence is particularly relevant in instances where the child experiences physical and/or psychological loss of one or both parents due to death of parent, abandonment by parent, significant mental or physical condition of parent, placement of child into foster care, termination of parental rights, adoption or alienation from parent often in the context of a contentious custody case. It has been observed that in order to achieve Psychological Permanence, the child at risk may need assistance in addressing various sources of inner conflict, confusion and ambivalence regarding his/her non-custodial, distant, temporarily or permanently absent parent. Furthermore, the child’s perspective of his/her relationship with the custodial parent (e.g. adoptive parent, parent with primary residential custody, long term foster parent) must be sufficiently congruent with what s/he envisions as the ideal family environment.

The Gries Assessment of Psychological Permanence (GAPP), initially developed in 1997, is designed to tap into the child’s perception of his actual and psychological relationship with his/her non-custodial parent(s) and with his/her custodial parent or caregiver. As with other self-report measures, the GAPP yields a subjective estimate of how the child understands and feels about the significant adults in his/her life. In Part I, the child is asked about his/her perspective of the non-custodial parent(s), whereas in Part II, the child is asked about his/her relationship with the custodial parent.

Part I is divided into 6 sections, totaling 35 questions. Section A looks at the degree to which the various losses experienced by the child have been successfully mourned. These losses may entail physical loss, genealogical loss, social status loss, and/or loss of part of oneself corresponding to the absent parent. Section B addresses the presence or absence of feelings of betrayal and rage as consequences of past mistreatment or disinterest attributed to the non-custodial parent. Section C pertains to the degree to which the child accepts blame for any felt estrangement from the non-custodial parent. Section D attempts to assess the child’s appreciation of the complexity inherent in his/her parent’s capabilities, deficits and personality. In contrast with the demonization of the distant or absent parent, often found in alienated children, the emotionally healthy child is apt to recognize the special qualities of both parents, as well as accept their limitations. Sections E and F reflect the outcomes of successful or unsuccessful resolutions of issues addressed in Sections A – D. Section E registers the child ‘s readiness to forgive others for disappointments experienced, as opposed to being preoccupied with a victim’s identity and need for vengeance. Section F explores the child’s vision of the future of his/her relationship with the distant/absent parent, and the degree to which such future outlook is governed by reality vs. fantasy factors.

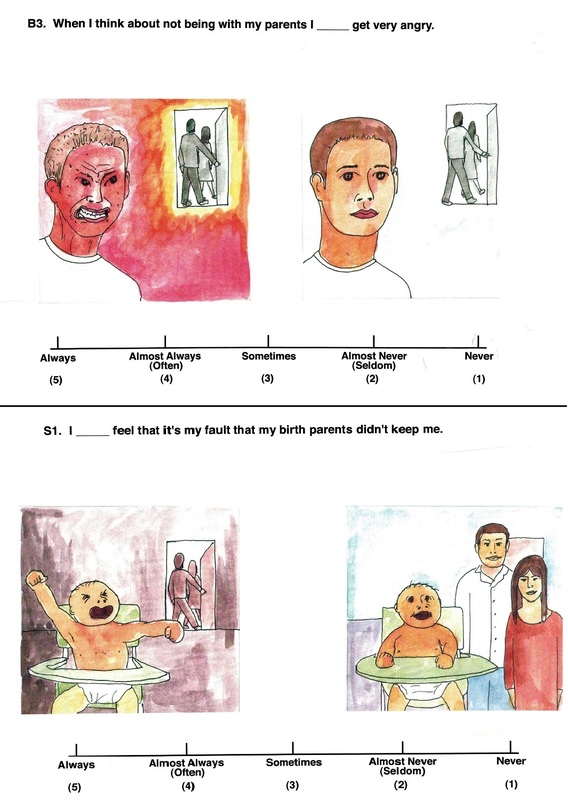

In the non-illustrated version of Part I, intended for children and adolescents between 11 and 18 years, the subject is asked to agree or disagree with each printed statement, on a 5 point continuum. E.g. always, almost always/often, sometimes, almost never/seldom, never, feel or think the way the statement reads. An illustrated version of Part I is administered to children between 5 and 11 years of age. Two examples are provided in the following pages. The first shows an item from Section B, which taps into lingering feelings of betrayal and anger that may be active in the child. The second shows an item from Section C, which taps into any lingering sense of self-blame that may be festering.

The examiner introduces Part II by mentioning how there are many things that contribute to a happy, loving and well-run family. Fourteen factors are identified and defined. They include: Unconditional acceptance, unconditional love, full family membership rights, safety and security, basic life necessities met, material needs met, age appropriate opportunities, personal growth support, respect and trust, fairness regarding rules and responsibilities, fair punishment, social freedom to enjoy outside relationships, access to outside help, and permanent commitment to abide by the first 13 factors. The child or adolescent is asked to compare his/her own family with what is described as the ideal level for each of the 14 factors. The child is asked to estimate how close to the ideal score of 7 his/her own family fares. What emerges is a line graph illustrating the ups and downs, the strengths and weaknesses that the child perceives within his/her family at the time of the assessment.

Leonard T. Gries, Ph.D. 1/18/2015

RSS Feed

RSS Feed